Kent Remembers: Colin Blythe

Sunday 14th November 2021

Born: 30.5.1879, Deptford. Died: 8.11.1917, Forest Hall to Pimmern military railway line near

Passchendaele, Belgium.

Kent 1899-1914. Cap (no.53), 1900.

Tests: 19 for England

Wisden Cricketer of the Year, 1904.

Colin ‘Charlie’ Blythe’s standing as one of the greatest exponents of classical left-arm spin has diminished over the last hundred years or so. Few of his contemporaries seem to have had doubts.

To Ranjitsinhji he was the best left-arm bowler he had ever faced, to Gilbert Jessop ‘the best left-handed bowler of my time, the most difficult and probably the most accurate’. One of his opponents, Charles Macartney, thought him ‘the best left-hander on English wickets I have ever seen’. ‘His remarkable flighting of the ball and his deception in pace are the best I ever met’.

Writing in 1909, Philip Trevor, manager when Blythe toured Australia with MCC in 1907/08 and one of the more technically knowledgeable of the pre-1914 generation of cricket pundits, put it simply, ‘better than any other bowler on a good wicket and much better than any other bowler on a bad wicket’.

Blythe took his 100 Test wickets at 18.63 each. Blythe’s hundred wickets came in just 19 Test matches. Shane Warne needed 23, Muttiah Muralitharan 27, Wilfred Rhodes 44.

When war ended Blythe’s first-class career in 1914, he had 2503 wickets.at 16.81. At this stage, Rhodes had 2735 wickets at 17.31.

The subject of two biographies as well as a book in the ACS Famous Cricketers Series, rather more is known of Blythe’s method than most bowlers of the period. Anyone interested can see his run up and action described at length complete with diagram in the Kent Messenger of 31 July 1909. Several sources refer to unusually long fingers, strengthened, according to Blythe himself, by hours practicing the violin.

One of his greatest assets was accuracy. In the nets, Blythe could reputedly land five balls out of six on a football placed on a length. His supreme quality however seems to have been flight. Numerous batters were lured into playing good length balls as half volleys or offering catches from balls pitching a foot shorter than expected.

A deep thinker about the game, he was, to quote the cricketer/journalist Teddy Sewell, ‘One of the last of the dying race willing enough and far seeing enough to give away two or three boundaries to get a wicket’.

On wet or worn pitches, he could be unplayable, but as well as the left-arm spinner’s stock delivery spinning away from the bat and the ball that went with his arm, on benign wickets he bowled a full medium-pace in-swinger, often a yorker.

He believed in bowling faster to quick-footed batters, and if a batter looked like settling, he would bowl from a yard or more behind the crease. If there was nothing in the wicket, he would sometimes switch to leg-theory with six or seven on the leg-side. To a batter reluctant to play strokes, he would on occasions try an in-swinging full toss aimed at the offbail. ‘Long Leg’ in the Kent Messenger rated an afternoon spent watching Blythe from behind the arm ‘an intellectual treat’.

Although he arrived with ‘no idea of batting’ according to William McCanlis, he developed into a competent batter, sharing in several valuable late- order partnerships.

At Trent Bridge in 1904 he put on 106 for the ninth wicket (Blythe 82*, Fairservice 50) and against Sussex at Canterbury in 1906 he assisted his captain Marsham in adding 111 in 35 minutes (Marsham 119, Blythe 53).

Colin Blythe was born in Evelyn Street, Deptford, the eldest of 13 children, seven boys, six girls, all but one of whom lived beyond infancy. There are conflicting accounts of when and how cricket entered ‘Charlie’ Blythe’s life but most agree that it was when he was aged around 11.

According to some accounts he played for his school; others refer to ‘boys’ clubs’ on Blackheath. Either way, his first cricket was almost certainly on primitive pitches on the broad expanse of Blackheath which could and did easily accommodate 20 or more matches at a time.

The story of Blythe’s joining Kent is well known. Christopher Sandiford in his ‘The Final Over, The cricketers of summer 1914’, asserts that Blythe ‘applied for a county trial largely to avoid working alongside his father as a fitter’ but this is at total variance with every other account, including Blythe’s own.

On Saturday 17 July 1897, he was at Rectory Field, Blackheath for the last day of Kent v Somerset. Some accounts suggest that this was his first county match but this seems unlikely given his age. Rectory Field and another regularly used Kent venue, Catford Bridge, were in walking distance (or a short tram ride) of his then home in Wotton Road, New Cross. Before play started Walter Wright came out to practice and asked Blythe to bowl to him.

In Blythe’s own words, ‘I don’t think there were more spectators than players’ but looking on was William McCanlis, Manager of the Tonbridge Nursery. He was impressed.

‘I spoke to him and arranged for him to come and bowl to me one evening’.

This he duly did in the nets of the Charlton Park Club where McCanlis was captain and the outcome was an invitation to a trial at the Nursery. The result appears in the Trial Book at Canterbury: ‘Bowls slow left. A very useful bowler.’ Blythe was taken on the staff in August 1897, carrying on at the Woolwich Arsenal munitions factory in the winter.

On 21 August 1899 he made his first-class debut, against Yorkshire at Tonbridge. Brought on as second change, he bowled Frank Mitchell leg stump with his first ball and retained his place for the remaining four matches of the season.

On his third appearance, against Surrey at Blackheath, his figures read 5.1-1-15-3 in the first innings, 24-16-24-3 in the second and included the wickets of Bobby Abel (bowled) and Tom Hayward (caught).

In the final match of the season at Hove he added the even more illustrious scalp of Charles Fry.

Wisden was non-committal, ‘he has not yet done enough to justify one predicting a great future for him’ but the 1900 season saw Blythe make, to quote Wisden again ‘a sudden jump to the front’.

With 114 wickets at 18.47 each, he was Kent’s leading wicket taker. Eleven times that year he claimed five or more in an innings, twice ten or more in a match. To Wisden he was ‘clearly one of the best slow bowlers in England.’

He excelled in his first Canterbury Week with 11 for 72 against Lancashire and six for 73 in Surrey’s only innings; two weeks later on the same ground he took 12 for 123 against Worcestershire.

During the 1900/01 winter Blythe returned to Woolwich Arsenal as usual but missed several weeks work due to an unspecified illness.

After an early taste of Test cricket in Australia (see below), Blythe returned to English cricket in 1902 fitter, stronger and probably wiser and, although Rhodes was preferred for the Test series, he excelled on the numerous rain-affected pitches in a very wet summer.

For the first time he claimed 100 wickets (111) in Championship matches alone and by the end of 1903, another wet one, he was firmly established in the very front rank of English spinners. 13 times he claimed five or more in an innings including his best analysis to date, nine for 67 against Essex at Canterbury. Wisden chose him as one of their Five Cricketers of the Year.

There can be little argument over Blythe’s status as a county cricketer. He was Kent’s leading wicket-taker in 1900, 1902 to 1905 inclusive and 1908 to 1914 inclusive.

Between 1900 and 1914 he headed the Kent bowling averages eight times and in each of his final two seasons he led the national averages. Apart from 1901, he exceeded 100 wickets in every season between 1900 and 1914.

In his eight final seasons his haul only once fell below 150, his highest 183 in 1907, 197 in in 1908 and 215 in 1909.

His most economical season was 1912 when his wickets cost 12.26, his most expensive the dry summer of 1911 when the cost rose to 19.38.

While statistically his most remarkable bowling was at Northampton in 1907 when he bowled Northants to defeat with ten for 30 & seven for 18 in a single day, given the quality of the opposition, he rarely bowled better than in 1903 when, in the space of five days, he took seven for 41 & five for 26 v Surrey at The Oval, bowling unchanged throughout the match, and six for 35 & seven for 26 v Yorkshire at Canterbury.

Possibly the best of many notable performances on bland and unhelpful wickets was at Old Trafford in 1914 where, as Lancashire compiled 475 from 148.1 overs, his figures were 52.1-14-138-7.

In addition to his 17 wickets at Northampton in 1907, he took 16 for 102 at Leicester in 1909 and 15 in a match three times of which perhaps the most significant was 15 for 99 for England v South Africa in 1907.

He claimed nine in an innings five times, nine for 67 v Essex, Canterbury 1903, nine for 30 v Hampshire, Tonbridge 1904, nine for 42 v Leicester 1909, nine for 44 v Northampton 1909, nine for 97 v Surrey, Lord’s,1914.

Blythe’s two hat-tricks were both in 1910, v Surrey at Blackheath and Derbyshire at Gravesend. Against Surrey he actually dismissed four in five balls and five in ten – Hayward from the first and Andy Ducat from the last ball of one over, Herbert Strudwick, William Abel and ‘Razor’ Smith from the second, third and fourth of the next.

Linked as it is with what is now widely assumed to be Blythe’s epilepsy, his career in Test cricket is worth examining in some depth. Test cricket came to him earlier than he or anyone else can have expected.

In 1899 when, MCC having turned down an invitation to send a team to Australia, MacLaren was faced with raising one as a private venture. It was hard going. Not only were most of the leading amateurs unwilling or unable to make the trip; half a dozen top professionals also refused.

The upshot was that Blythe, with only 48 matches and a little over 1,800 first-class overs under his belt, was chosen in place of Rhodes. He had not had an outstanding season in 1901 and the selection was not without its critics.

Ranjitsinhji, soon to be one of Blythe’s greatest admirers, predicted he ‘would never get a wicket’.

Blythe began well with five for 45 v South Australia at Adelaide and three for 26 & four for 30 in the First Test at Sydney, the latter earning him an engraved gold pocket watch. Despite the handicap of a split spinning finger, his good form continued with four for 64 in the first innings of the Second Test at Melbourne but he suffered further injury to his bowling hand and was advised by a doctor to rest.

However, MacLaren, never the most considerate of skippers, was short of bowling and a handicapped Blythe played for the rest of the series.

According to Jessop in his ‘A Cricketer’s Log’, in the third Test, Blythe delivered the ball from the palm of this hand and in the fourth bowled with two fingers strapped together. His figures make instructive reading – 12 for 205 in the first two Test matches, six for 265 in the remaining three.

‘Charlie’ Blythe experienced cricket overseas again at the end of the 1903 season when Kent broke new ground by touring the USA, the first county to tour outside the UK.

He was one of four professionals who for ‘expenses and a ten pound note’ offered to join what was originally envisaged as an all-amateur venture. Although unwell for much of the tour, he nevertheless took 23 inexpensive wickets, ten of them now recognised as first-class.

In 1905, Blythe tasted Test cricket in England for the first time, when chosen against the Australians at Headingley as a replacement for the injured Rhodes. Little used in the first innings, his three for 41 from 24 overs in the second gave England a brief hope of victory as Australia played out time.

In the winter he toured South Africa with MCC under Pelham Warner. The team was not fully representative and England lost the series by four matches to one but, while most of the batters struggled on matting wickets, Blythe contributed hugely to England’s only victory with six for 68 & five for 50 in the Fourth Test at Cape Town. He was second in the Test averages with 21 wickets (avge.26.09) and 57 (avge. 18.35) in all first-class fixtures.

During the tour Blythe was impressed by C.J.Nicholls, a young fast bowler of Malayan extraction who bowled to MCC in the nets, but family opposition prevented the young man from accepting Blythe’s invitation to come over for a trial.

When South Africa toured in 1907, Blythe played in all three Test matches, selected for the first time ahead of Rhodes. Split webbing on his left-hand acquired in attempting a catch at mid-off in the first Test at Lord’s meant bowling throughout almost the entire match under the handicap of strapping and in the circumstances two for 18 & two for 56 was a satisfactory return.

In the second Test at Headingley, played throughout on a rain-affected wicket, Blythe produced his, statistically at least, finest performance in Test cricket. After England had been dismissed for 76 he bowled them back into the game with eight for 59 although, interestingly, Wisden judged ‘he was not quite so accurate in length as he might have been’. On the last day with the tourists needing only 129 he skittled them for 75, his figures – 22.4–9–40–7. The only spinner in the side, he bowled unchanged except for one over and suffered at least three dropped catches. Ten of his victims were caught, three lbw, two stumped.

In the light of Wisden’s comment it is worth noting that Fry in his autobiography ‘Life Worth Living’ insists: ‘from start to finish he never bowled a single ball except of impeccable length’. Blythe had, to quote Wisden, again, ‘almost bowled himself to a standstill’; Fry described him as ‘completely knocked up’.

In 1907, epilepsy, if such it was, was little understood and seldom spoken of and it seems likely that this was its first semi-public manifestation.

Although Blythe joined Kent for their next match at Worcester, one for 143 suggests he was some way off his best and he was rested from the following fixture, the first of Canterbury Week.

When he returned for the second, against Lancashire, his three wickets cost 170 runs but normal service soon resumed with five for 69 v Gloucestershire at Cheltenham and seven for 45 v Somerset at Taunton. The Oval Test match was also affected by rain.

On a drying wicket, Blythe was below par on the first evening finishing one for 47 but returned to his best on the second morning with four for 14 as the last five South African wickets fell for 29. He headed the bowling averages for the series with 26 wickets (avge.10.38).

Both Rhodes and Blythe were chosen for the 1907/08 MCC tour of Australia, but after playing in the First Test in which he took only one expensive wicket, Blythe was not picked again. In all first-class matches he took 41 wickets at 22.80 including 11 for 83 against Queensland and actually ended with a better record than Rhodes – 31 at 27.00.

In 1909, Blythe marked his benefit year with 215 wickets in all matches, 178 in Championship matches – his personal best in both cases. Both Blythe and Rhodes were chosen for the first Test match against Australia at Edgbaston but in the event the Yorkshireman bowled only one over, Blythe (six for 44 & five for 58) and Hirst (four for 28 & five for 58) bowling unchanged through the first innings and all but five overs of the second. Given the opposition, this was arguably Blythe’s greatest Test match but the aftermath would reverberate for the rest of his career.

In the next fixture, against Middlesex at Lord’s, he felt faint after bowling one over and was taken off although he remained on the field. After an hour or so he was back to normal and finished with six for 37. He again started shakily at Old Trafford but, carefully nursed by Ted Dillon, he returned after a rest to bowl superbly for seven for 57.

Blythe was in the 13 for the Second Test at Lord’s but Dillon and the Kent committee were clearly worried and called in a specialist. The outcome was a telegram from Lord Harris to the acting Chairman of Selectors, ‘Shrimp’ Leveson Gower. ‘Specialist strongly advises Blythe ought not to play on Monday but is quite hopeful he will be fit for the remaining Tests if wanted’. The specialist concerned was Sir William Gowers (1845-1950), at the time the foremost authority on epilepsy and author of several books on the subject. His Manual of Diseases of the Nervous Systems, known as the ‘Bible of Neurology’, is still widely- read. The Sir William Gowers Centre in Chalfont St Peters, part of the charity the Epilepsy Society and now run by the University Colleges London NHS Foundation Trust, is named after him.

In the period between the First and Second Tests Blythe had taken 26 wickets at 15.65 but in the match at Tonbridge against Worcestershire, starting 14 June and played over the same three days as the Lord’s Test, he apparently had ‘a fit’ on the second evening and returned home. At that point Worcestershire had batted twice, Blythe had bowled 65 overs and picked up nine wickets. On the final day, as Kent declined from 51 for one overnight to 108 all out, Blythe, batted and was bowled for one.

Over the next two days, still at Tonbridge, he bowled 61 overs and took four for 226 against Lancashire. If this was some way below par, three days later he bowled unchanged with Arthur Fielder to dismiss Gloucestershire for 61 at Catford (Fielder six for 34, Blythe four for 20).

Meanwhile, for reasons which need not concern us here, the selectors, Leveson Gower, Fry and MacLaren, were on the receiving end of a storm of vituperation from the press and others. At the end of the season Wisden joined in, accusing the selectors of decisions that ‘touched the confines of lunacy’ ‘Never in the history of Test matches in England has there been such blundering in the selection of an England eleven’. In defence of the selectors but with sublime disregard for patient confidentiality, Sir William Gowers’ report was made public:

Mr Blythe, whom I have seen this morning, suffers from the strain on his nervous system caused by playing in a Test match, and the effect lasts for about a week afterwards. It is desirable that he should take a temporary rest from the work, and should not play in the coming match at Lord’s. If this can be arranged there is good hope that with treatment his difficulty will pass away. It does not exist in the case of county matches.

Although fit for the Third Test match at Headingley, he was not chosen. While England were losing by 126 runs, Kent were beating Northants by 125 runs at Gravesend (Blythe six for 49 & one for 41).

Whatever his state of health, in the nine matches in the period between the end of Tonbridge Week in which he suffered his ‘fit’ and the next time the selectors called on his services Blythe garnered 72 wickets at 12.77 apiece, eight times five in an innings, three times ten in a match including five for 48 & seven for 55 for Players v Gentlemen at The Oval, the only time he appeared in what was then still in the eyes of many, the high point of the season.

In what proved to be his last home Test match, Blythe returned to the team for Old Trafford and, in tandem with Sydney Barnes, bowled superbly in the first innings (Barnes five for 56, Blythe five for 63) but did less well (two for 77) in the second innings when Rhodes (five for 83) was the pick of the bowlers as the game subsided into a draw. He was one of the 13 for the Fifth Test match at The Oval but was left out of the final eleven.

Blythe was selected for the 1909/10 MCC tour of South Africa but the captain, Leveson Gower revealed in his memoirs that he did not want him, ostensibly because there were two other left-arm spinners, Rhodes and Frank Woolley, in the party, both deemed better batters.

Despite seven for 20 v Natal and five for 21 v Eastern Province, Blythe did not get into the Test side until the Fourth Test match but he emerged with far the better record – in Test matches: 12 wickets (avge. 14.00), Rhodes, two (avge. 73.50), Woolley seven (avge.35.85). In all first-class matches; Blythe took 50 wickets (avge.15.66), Rhodes 21 (25.47), Woolley 15 (avge.30.53).

Together with the batting of Hobbs and Rhodes, Blythe’s seven for 46 & three for 58 in the final Test match at Cape Town was decisive in England’s nine-wicket victory and, if nothing else, ensured that his Test career ended on a suitably high note.

Blythe’s problems were not it seems entirely confined to Test matches.

In a much publicized incident during the 1911 Canterbury Week he was accused by Charles Fry, quite wrongly according to all the evidence, of deliberately bowling full tosses out of the sun (a full account can be found in the Kent County Cricket Club Annual 1992 pp 41-44) Although virtually the entire cricketing community supported Blythe, the incident affected him and he missed the second match of the Week against Lancashire, his friend ‘Pip’ Fielder’s benefit.

Although arguably still the best spinner in the country, Blythe was not chosen for any of the six home Test matches staged in the four years remaining before the outbreak of war or for the MCC tours to Australia in 1911/12 or South Africa in 1913/14.

In the early years of the 20th century mental health, nervous disorders and related matters tended to be swept under the carpet and rarely talked about outside an enlightened minority which makes it difficult to avoid the suspicion that his health may have had a bearing on selectorial decisions.

Oddly enough, it seems to have been generally overlooked that, other than Lord’s in 1909, Blythe never actually turned down an invitation to play in a Test match. Apart from a remark to his violin teacher, Leonard Furnival, and a statement by the South African all-rounder Gordon White that ‘Charlie Blythe hated Test matches‘ there seems to be no actual evidence that the man himself ever expressed a view one way or the other.

In the Wisden obituary Sydney Pardon referred to a ‘tendency to epileptic fits’ and the consensus now seems to be that some form of epilepsy was the problem. Not everyone agrees, notably his biographer John Blythe Smart, a member of the extended family, and it has to be said that, as far as can be discovered, no suitably qualified medical authority ever used the word.

Some authors since have preferred ‘nervous disposition’ ‘highly strung’ ‘temperamental’ etc. Simon Sweetman in his Dimming of the Day, (ACS Publications), published in 2014, described Blythe as effective at Test level ‘when he could bring himself to play’.

Patrick Morrah, in his Golden Age of Cricket published in 1967, went rather further. To him Blythe was ‘sensitive, shrinking, neurotic’. Shrinking violets do not flourish in Deptford‘s soil and these were odd words to use for a man who volunteered for the Army when experience at Woolwich Arsenal could have kept him at home.

Still less for one promoted Sergeant after little more than a year in the Army.

Somewhat different but equally puzzling, Christopher Sandiford in his book published in 2014 (see above) without naming his sources, asserts that Blythe ‘would sometimes work himself into a state approaching hatred of the batters’. Fielders if they watched closely enough, could hear him muttering to himself and see him clenching his jaw.

None of this seems to bear any relation to what was written of Blythe during his career and immediately following his death by those who played with and against him. Dick Lilley, who played against him on numerous occasions and toured Australia with him, in his Twenty Four years of Cricket (Mills & Boon, 1912) writes:

‘He is also one of the most pleasant fellows it is possible to meet. He never seems to mind if a batsman hits him for a few fours but on the contrary does not always discourage him from attempting this as he knows it often gives him a better opportunity of getting his wicket. I have never, under any circumstances seen him lose his temper; he is always too keen on getting as much pleasure out of the game as possible’.

When Hampshire’s South African allrounder Charles ‘Buck’ Llewellyn hit him for five sixes, Blythe was reported as saying ‘Charles. I would give all my bowling to be able to bat like that’ and a similar story is told of his reaction to suffering at the hands of the supreme stylist, Reggie Spooner.

Another who batted against him, Harry Altham, wrote in his A History of Cricket (Allen & Unwin, 1926) ‘here was bowling raised from a physical activity on to a higher plane. The very look on his face, the long sensitive fingers, the long last stride – all these spoke of a highly sensitive and nervous instrument, beautifully co-ordinated, directed by a subtle mind‘. From his Kent colleagues, – ‘even tempered’, ‘genial,’ easy-going’ ‘sterling character’, ‘heart & head of a lion’, ‘calm, reflective and unflinching’ were just some of the terms used.

Nor do Charlie Blythe’s off-the-field interests fit the ‘shrinking’ image. As well as a love of boxing – ‘he would pay five guineas to see a good fight’ he was no stranger to the race track, played football and, after he moved there, turned out on occasions for Tonbridge Town. On his first tour of Australia he formed a formidable half-back line with John Tyldesley and Willie Quaife when England beat Freemantle 4-0. He also skated; his last holiday was for winter sports at Chamonix in early 1914.

In the days before radio and television, the ability to play a musical instrument was not an uncommon skill but, as a violinist, Charlie Blythe was clearly well above front parlour standard. In his latter years from October to March he practiced every day for two hours and owned two violins, one made in Italy for which he paid £80. One of his bows was by the celebrated bow maker Alfred Tubbs who presented it to him in recognition of his bowling at Leeds in 1907.

In March 1907 at Greenwich Registry Office, Colin Blythe married Janet Gertrude Brown from Tunbridge Wells, almost ten years his junior.

While living with the family, he had played with the orchestra at the long defunct New Cross Empire but after moving he was able to indulge his love of classical music as a first violin in the Tonbridge Symphony Orchestra, conductor the former Kent batter Dr Haldane Stewart. After one performance of the final movement of Mozart’s Sixth Symphony, Stewart named Blythe as ‘the nimblest player in the orchestra’.

Blythe played his last first-class match, against Middlesex at Lord’s on 27 and 28 August 1914, taking five for 77 & two for 48 as Kent lost in two days.

Following the outbreak of war, married men were in the early days under no great pressure to enlist and, with his health issues and his experience in the armament industry, he could easily have avoided military service.

Nevertheless, Blythe, alongside Henry Preston, David and Tom Jennings and Frank Woolley’s brother Claud, enlisted in a Territorial Army unit, the Kent Fortress Engineers, and he missed Kent’s final game of the season at Bournemouth. He joined Number One Reserve Company in Tonbridge.

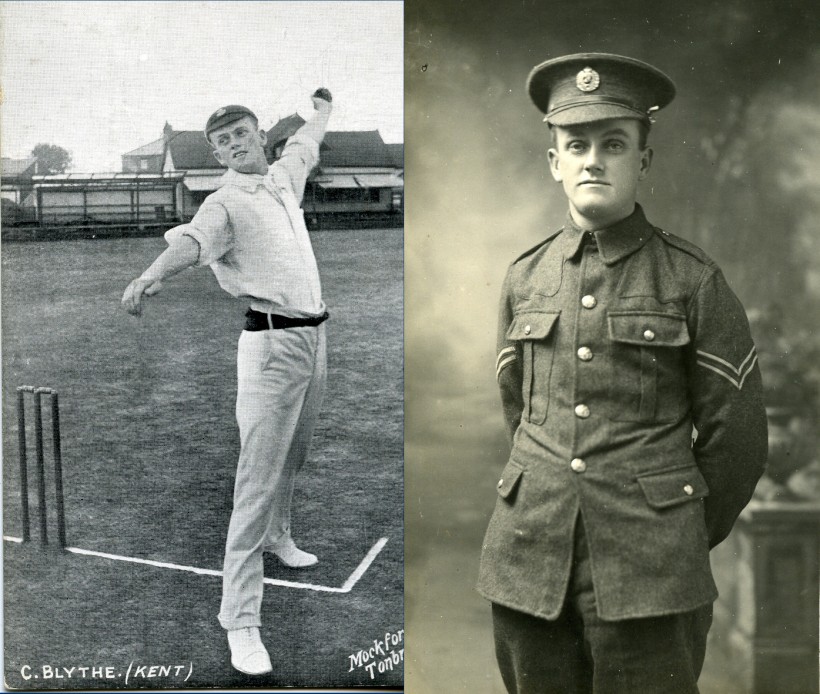

Claud Woolley (L) and Colin Blythe (R) both enlist for the Kent Fortress Engineers (KFE) on the outbreak of the First World War in July 1914. (Colourised)

In October, Blythe and his fellow recruits were posted to the Woodlands depot in Gillingham.

According to the Tunbridge Wells Advertiser, who sent a reporter to see them off, Blythe was the life and soul of the party’.

Promoted Corporal at the end of 1914 and Sergeant in the following year, he remained at Gillingham for two years with 2/7 Reserve Company working on coastal defence and construction tasks.

While at Gillingham, Blythe was involved with C. Woolley and Bill Fairservice in the formation of the KFE cricket team which, with seldom less than four county cricketers, proved too strong for most local opposition. In their first game, when a RE side was beaten by an innings he took three for 33 & four for 3, followed by seven for 36 against a South African Eleven at Gravesend and match figures of 14 for 85 v Chatham Garrison.

Following the introduction of conscription in 1916, all Territorials were obliged to sign Imperial Service Forms and became liable for service overseas.

Early in 1917, Blythe and Woolley were among a party posted to Marlow for further training.

While there Blythe, Woolley, Jennings and others played for Royal Engineers (East Anglia). Unsurprisingly, Blythe was too much for the opposition – nine for 33 v RNAS (Transport), seven for 26 v RE (Regent’s Park), seven for 13 v Royal Naval Division.

He also played his last match at Lord’s, for Navy & Army v Australian & South African Forces in aid of Lady Lansdowne’s Officers’ Families Fund. Not fully fit, his figures were 14-2-54-1, his last wicket, Charles McCartney.

In September, a party of Kent Fortress Engineers from Marlow, including Sergeant Blythe and Corporal Woolley, were among 277 soldiers who sailed to France as reinforcements for the 12th (Pioneer) Battalion of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (31 Division).

In John Blythe Smart’s biography it is suggested that, following his younger brother Sidney’s death on the Somme in September 1916, Colin Blythe had asked for a transfer to an active unit but as some 30 others from the KFE were posted at the same time, this seems unlikely.

However, the local Marlow paper carried a story that he had offered to take a step down in rank to ensure he was not left behind which might indicate he was not an original choice.

Arriving in early October, the new draft was posted to Watou for a course in light railway construction and maintenance, an activity in which the 12th Battalion specialised.

On re-joining the Battalion, B Company began work on the Wieltje (Forest Hall) and Bedlington lines near Passchendaele.

On the night of 8 November, a shell from a long range gun burst above a working party killing three, wounding six with one missing.

Sergeant Blythe was killed instantly by shell splinters, Corporal Woolley was among the wounded.

Colin Blythe is buried in Oxford Road cemetery and is commemorated on the memorial at The Spitfire Ground, St Lawrence in Canterbury as well as on a plaque in Tonbridge Church.

In every Canterbury Cricket Week the memorial is the site of a simple wreath-laying ceremony.

Profile adapted from Derek Carlaw’s ‘Kent County Cricketers: A to Z, 1919-1939’

Previous profiles of Kent Cricketers that fell during both World Wars include:

Colin Blythe

Gerry Chalk

Arthur Du Boulay

Eric Hatfeild

Kenneth Hutchings

David Jennings

Lawrence Le Fleming

Geoffrey Legge

Lionel Troughton

George Whitehead